What Money Was Used In 1616 In America

Early American currency went through several stages of development during the colonial and postal service-Revolutionary history of the The states. John Hull was authorized by the Massachusetts legislature to make the earliest coinage of the colony, the willow, the oak, and the pine tree shilling in 1652.[1]

Since there were few coins minted in the Thirteen Colonies, that later became the United States, foreign coins like the Spanish dollar were widely circulated. Colonial governments, at times, issued paper coin to facilitate economic activities. The British Parliament passed Currency Acts in 1751, 1764, and 1773, that regulated colonial paper money.

During the American Revolution, the Colonies became independent states. No longer subject to arbitrarily imposed monetary regulations by the British Parliament, u.s.a. began to issue newspaper money, to pay for military expenses. The Continental Congress also issued paper money during the Revolution—known as 'Continental currency'—in society to fund the war effort. Both Land and Continental currency depreciated chop-chop becoming, in consequence, worthless by the end of the war. This depreciation was caused by the government, stemming from the printing of big amounts of currency, in their effort to meet the budgetary demands of the state of war. Additionally, British counterfeit gangs contributed further to the decreased value. By its conclusion, only a few counterfeiters had been caught and preemptively hanged, for the criminal offense.

Colonial currency [edit]

There were 3 general types of coin in the Colonies of British America: the specie (coins), printed paper money and merchandise-based article money.[ii] Commodity money was used when greenbacks (coins and newspaper money) were deficient. Commodities such as tobacco, beaver skins, and wampum, served equally money at diverse times in many locations.[3]

Cash in the Colonies was denominated in pounds, shillings, and pence.[three] The value of each denomination varied from Colony to Colony; a Massachusetts pound, for instance, was not equivalent to a Pennsylvania pound. All colonial pounds were of less value than the British pound sterling.[3] The coins in circulation during the Colonial Era were, most oftentimes, of Spanish and Portuguese origin.[3] The prevalence of the Spanish dollar throughout the Colonies, led to the money of the United States being denominated in dollars, rather than pounds.[3]

1 past i, colonies began to result their ain paper money to serve as a convenient medium of exchange. In 1690, the Province of Massachusetts Bay created "the start authorized paper coin issued by any government in the Western World".[4] This newspaper coin was issued to pay for a military expedition during King William's War. Other colonies followed the case of Massachusetts Bay by issuing their own paper currency in subsequent military machine conflicts.[iv]

The paper bills issued by the colonies were known as "bills of credit". Bills of credit were commonly fiat money: they could non be exchanged for a fixed corporeality of aureate or silver coins upon demand.[three] [v] Bills of credit were usually issued by colonial governments to pay debts. The governments would and then retire the currency past accepting the bills for payment of taxes. When colonial governments issued likewise many bills of credit or failed to tax them out of circulation, inflation resulted. This happened especially in New England and the southern colonies, which, dissimilar the Middle Colonies, were frequently at war.[5] Pennsylvania, nonetheless, was responsible in not issuing too much currency and it remains a prime number instance in history every bit a successful government-managed monetary system.[ citation needed ] Pennsylvania's paper currency, secured by land, was said[ by whom? ] to accept generally maintained its value against golden from 1723 until the Revolution broke out in 1775.[ citation needed ]

This depreciation of colonial currency was harmful to creditors in Great United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland when colonists paid their debts with money that had lost value. The British Parliament passed several Currency Acts to regulate the paper coin issued by the colonies. The Human activity of 1751 restricted the event of paper money in New England. It immune the existing bills to be used equally legal tender for public debts (i.e. paying taxes), but disallowed their utilize for private debts (e.g. for paying merchants).[half dozen] In 1776, British economist Adam Smith criticized colonial bills of credit in his most famous work, The Wealth of Nations.

Another Currency Act, in 1764, extended the restrictions to the colonies south of New England. Different the earlier human activity, this human activity did not prohibit the colonies in question from issuing paper coin but it forbade them to designate their currency every bit legal tender for public or private debts. That prohibition created tension between the colonies and the mother country and has sometimes been seen equally a contributing factor in the coming of the American Revolution. Afterwards much lobbying, Parliament amended the act in 1773, permitting the colonies to issue paper currency equally legal tender for public debts.[7] Soon thereafter, some colonies once again began issuing paper money. When the American Revolutionary War began in 1775, all of the insubordinate colonies, soon to exist independent states, issued paper money to pay for military expenses.

Xiii colony set up of U.s. Colonial currency [edit]

The Xiii Colony set of colonial currency beneath is from the National Numismatic Drove at the Smithsonian Institution. Examples were selected based on the notability of the signers, followed past issue engagement and condition. The initial selection criteria for notability was fatigued from a listing[eight] of currency signers who were as well known to take signed the U.s. Declaration of Independence, Articles of Confederation, the The states Constitution, or attended the Stamp Act Congress.[nb ane]

| Colony | Value | Date | Issue | Showtime[nb 3] | Note (obv) | Note (rev) | Signatures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

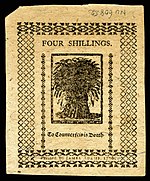

| Connecticut | 40s (£2) | 1775-01-02 | £fifteen,000[10] | 1709[11] |  |  | Elisha Williams, Thomas Seymour, Benjamin Payne[nb 4] |

| Delaware | 4s | 1776-01-01 | £30,000[13] | 1723[14] |  |  | John McKinly, Thomas Collins, Boaz Manlove |

| Georgia | $40 | 1778-05-04 | £150,000[nb 5] | 1735[xvi] |  |  | Charles Kent, William Few, Thomas Netherclift, William O'Bryen,[nb vi] Nehemiah Wade |

| Maryland | $1 | 1770-03-01 | $318,000[nineteen] | 1733[20] |  |  | John Clapham, Robert Couden[nb 7] |

| Massachusetts | 2s | 1741-05-01 | £50,000[22] | 1690[23] |  |  | Robert Choate, Jonathan Hale, John Brown, Edward Eveleth |

| New Hampshire | $i | 1780-04-29 | $145,000[24] | 1709[11] |  |  | James McClure, Ephraim Robinson, Joseph Pearson,[nb 8] John Taylor Gilman (rev) |

| New Jersey | 12s | 1776-03-25 | £100,000[26] | 1709[27] |  |  | Robert Smith, John Hart, John Stevens Jr. |

| New York | 2s | 1775-08-02 | £2,500[28] | 1709[29] |  |  | John Cruger Jr., William Waddell[nb 9] |

| Northward Carolina | £3 | 1729-11-27 | £40,000[31] | 1712[32] |  |  | William Downing,[nb 10] John Lovick,[nb 11] Edward Moseley, Cullen Pollock,[nb 12] Thomas Swann[nb thirteen] |

| Pennsylvania | 20s (£1) | 1771-03-20 | £15,000[36] | 1723[37] |  |  | Francis Hopkinson, Robert Strettell Jones, William Fisher[nb 14] |

| Rhode Isle | $ane | 1780-07-02 | £39,000[39] | 1710[40] |  |  | Caleb Harris, Metcalf Bowler,[nb fifteen] Jonathan Arnold |

| S Carolina | $threescore | 1779-02-08 | $ane,000,000[42] | 1703[43] |  |  | John Scott, John Smyth, Plowden Weston[nb xvi] |

| Virginia | £3 | 1773-03-04 | £36,384[45] | 1755[46] |  |  | Peyton Randolph, John Blair Jr., Robert Carter Nicholas Sr.(rev) |

Continental currency [edit]

Continental I Third Dollar Annotation (obverse)

A fifty-five dollar Continental issued in 1779

After the American Revolutionary State of war began in 1775, the Continental Congress began issuing newspaper money known every bit Continental currency, or Continentals. Continental currency was denominated in dollars from $ i⁄6 to $fourscore, including many odd denominations in betwixt. During the Revolution, Congress issued $241,552,780 in Continental currency.[47]

The Continental Currency dollar was valued relative to usa' currencies at the following rates:

- five shillings – Georgia

- 6 shillings – Connecticut , Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Virginia

- seven ane⁄two shillings – Delaware, Maryland, New Bailiwick of jersey, Pennsylvania

- 8 shillings – New York, North Carolina

- 32 i⁄ii shillings – Due south Carolina

Continental currency depreciated badly during the war, giving rise to the famous phrase "non worth a continental".[48] A master problem was that monetary policy was not coordinated between Congress and the states, which connected to issue bills of credit.[49] "Some think that the rebel bills depreciated because people lost confidence in them or because they were not backed by tangible avails," writes financial historian Robert E. Wright. "Not so. At that place were simply too many of them."[l] Congress and usa lacked the will or the means to retire the bills from circulation through revenue enhancement or the sale of bonds.[51]

Another trouble was that the British successfully waged economic warfare by counterfeiting Continentals on a large calibration. Benjamin Franklin later wrote:

The artists they employed performed so well that immense quantities of these counterfeits which issued from the British regime in New York, were circulated among the inhabitants of all the states, earlier the fraud was detected. This operated significantly in depreciating the whole mass.[52]

By the end of 1778, Continentals retained from one⁄5 to 1⁄7 of their confront value. By 1780, the bills were worth 1⁄40 of their face value. Congress attempted to reform the currency past removing the old bills from apportionment and issuing new ones, without success. By May 1781, Continentals had become so worthless that they ceased to circulate as money. Franklin noted that the depreciation of the currency had, in effect, acted as a taxation to pay for the war.[53]

For this reason, some Quakers, whose pacifism did not allow them to pay war taxes, also refused to apply Continentals, and at least 1 Yearly Meeting formally forbade its members to utilize the notes.[54] In the 1790s, later on the ratification of the The states Constitution, Continentals could be exchanged for treasury bonds at ane% of face value.[55]

After the plummet of Continental currency, Congress appointed Robert Morris to be Superintendent of Finance of the The states. Morris advocated the cosmos of the first financial institution chartered by the United States, the Depository financial institution of North America, in 1782. The bank was funded in function past bullion coins loaned to the Us by France.[56] Morris helped finance the terminal stages of the war by issuing notes in his proper name, backed by his personal line of credit, which was further backed by a French loan of $450,000 in silverish coins.[57] The Bank of Northward America besides issued notes convertible into gold or silver.[58] Morris too presided over the cosmos of the offset mint operated past the U.S. government, which struck the first coins of the The states, the Nova Constellatio patterns of 1783.[59]

The painful experience of the runaway inflation and plummet of the Continental dollar prompted the delegates to the Ramble Convention to include the golden and silverish clause into the United States Constitution then that the individual states could not result bills of credit or "brand any Thing simply gold and silvery Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts".[60] However, in Juilliard v. Greenman the Supreme Court of the U.s. settled an ongoing and very heated debate on whether this restriction of issuing bills of credit was likewise extended to the Federal government:

"By the constitution of the United states of america, the several states are prohibited from coining coin, emitting bills of credit, or making anything but aureate and silver coin a tender in payment of debts. But no intention tin exist inferred from this to deny to congress either of these powers."[61]

Come across as well [edit]

- Economic history of the The states

- Federal Reserve Note

- History of economic thought

- History of the United States dollar

- Monetary policy

- Money creation

- United states of america dollar

- Hyperinflation

References [edit]

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ Visually bonny and early examples were digitized and additional signer research was conducted later.

- ^ Obverse and reverse images take been prepared separately for table training purposes. Some of the notes obverse/reverse are not on the same orientation which would make single images containing both distracting.

- ^ Date of the first issue of paper currency for each of the Colonies.

- ^ Williams, Seymour, and Payne (among others) were appointed to a commission to print and sign currency for the Colony of Connecticut in the amount of 50,000 pounds.[12]

- ^ Newman (2008) indicates the total issue in Pound sterling despite the currency outcome in dollars.[15]

- ^ O'Bryen, Treasurer of Georgia,[17] was elected to the Continental Congress only did not attend.[18]

- ^ Couden served as Mayor of Annapolis from 1785–86 and 1790–91.[21]

- ^ Act authorizing Ephraim Robinson and Joseph Pearson to countersign New Hampshire currency.[25]

- ^ Waddell was a New York Urban center Alderman (1773–77) with the authority to sign currency issued to fund the "water works" under structure about Broadway and Chambers streets.[xxx]

- ^ Downing served as Speaker of the House of Burgesses from 1735 to 1739.[33]

- ^ Lovick was a member of the House of Burgesses.[34]

- ^ Pollock was a member of the House of Burgesses.[35]

- ^ Swann served equally Speaker of the House of Burgesses in 1729.[33]

- ^ Hopkinson, Jones, and Fisher authorized to sign Pennsylvania currency.[38]

- ^ Act passed June 1780 authorizing Harris and Bowler to sign Rhode Island currency.[41]

- ^ Scott, Smyth, and Weston (amidst others) were appointed commissioners with the authority to print and sign ane million dollars of S Carolina currency.[44]

These references have been removed from EH.Net ---

- ^ https://world wide web.waymarking.com/waymarks/WMDJHN_The_Hull_Mint_Boston_MA

- ^ Flynn, "Credit in the Colonial American Economy" Archived 2022-06-12 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c d e f Michener, "Money in the American Colonies" Archived 2022-06-eleven at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Newman, 1990, p. xi.

- ^ a b Wright, p. 45.

- ^ Allen, pp. 96–98.

- ^ Allen, p. 98.

- ^ Newman, 2008, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Friedberg & Friedberg, pp. 12–29.

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 110.

- ^ a b Newman, 2008, p. 89.

- ^ Public Records, May, 1775, The public records of the Colony of Connecticut 1636–1776, 1890, retrieved Apr 29, 2022

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 125.

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 119.

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 151.

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 130.

- ^ Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, Volume 11, Government Printing Office, 1908, retrieved April 29, 2022

- ^ Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774–2005, Government Printing Role, 2005, ISBN9780160731761 , retrieved April 29, 2022

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 172.

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 167.

- ^ Robert Couden, Maryland State Archives, retrieved April 29, 2022

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 200.

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 183.

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 223.

- ^ An Act describing the tenor of notes and certificates to be issued by the Treasurer of this state and appointing a committee to counter sign said notes, Laws of New Hampshire: Get-go ramble period, 1784–1792, 1916, retrieved Apr 29, 2022

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 260.

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 247.

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 285.

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 269.

- ^ Colonial And Revolutionary Families Of Pennsylvania, Laws of New Hampshire: First constitutional period, 1784–1792, 2004, ISBN9780806352398 , retrieved April 29, 2022

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 315.

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 313.

- ^ a b Due north Carolina State Firm of Representatives – By Speakers of the Firm, Colonial and Land Records of Northward Carolina, retrieved April 29, 2022

- ^ Letter from George Burrington to the Board of Trade of Cracking Uk, Documenting the American South, retrieved Apr 29, 2022

- ^ Minutes of the Upper House of the Northward Carolina General Assembly, Documenting the American South, retrieved April 29, 2022

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 346.

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 331.

- ^ The Statutes at Large of Pennsylvania from 1682 to 1801, Volume 8, State Printer of Pennsylvania, 1902, retrieved April 29, 2022

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 399.

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 371.

- ^ Records of the Colony of Rhode Isle and Providence Plantations, in New England, Alfred Anthony, Printer to the Land, 1864, retrieved April 29, 2022

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 426.

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 405.

- ^ An ordinance for the printing, stamping and issuing i million dollars…, Statutes at Big of Due south Carolina: Acts, 1753 – 1786, 1838, retrieved April 29, 2022

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 443.

- ^ Newman, 2008, p. 437.

- ^ Newman, 1990, p. sixteen.

- ^ Newman, 1990, p. 17.

- ^ Wright, p. fifty.

- ^ Wright, p. 49.

- ^ Wright, 52

- ^ Kenneth Scot, Counterfeiting in Colonial America (Philadelphia: Academy of Pennsylvania Printing, 2000), 259–60.

- ^ Wright, p. 49; Newman, 1990, 17.

- ^ Gross, David One thousand. (2014). 99 Tactics of Successful Tax Resistance Campaigns. Picket Line Press. p. 166. ISBN978-1490572741.

- ^ Newman, 1990, p. 17; Wright, p. 49.

- ^ Nuxoll, Elizabeth. "The Banking concern of North America and Robert Morris's Direction of the Nation'southward First Financial Crisis" (PDF). Papers of Robert Morris. University of Pittsburgh Press: 162. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ Unger, Harlow (12 March 2022). "How Robert Morris'south "Magick" Money Saved the American Revolution". Journal of the American Revolution . Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ Wright, p. 62.

- ^ Morris Papers, Volume 7, pp. 761–765

- ^ U.S. Constitution, Article I, section 10.

- ^ Juilliard v. Greenman, 110 U.South. 421, iv S.Ct. 122, 28 L.Ed. 204 (1884)

Flynn, David. "Credit in the Colonial American Economy". EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. March sixteen, 2008. Michener, Ron. "Money in the American Colonies". EH.Internet Encyclopedia, edited past Robert Whaples. June viii, 2003.

Bibliography [edit]

- Allen, Larry. The Encyclopedia of Money. 2nd edition. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO, 2009. ISBN 978-1-59884-251-7.

- Flynn, David. "Credit in the Colonial American Economy". EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited past Robert Whaples. March xvi, 2008.

- Michener, Ron. "Money in the American Colonies". EH.Cyberspace Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. June 8, 2003.

- Newman, Eric P. The Early on Paper Money of America. 3rd edition. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications, 1990. ISBN 0-87341-120-10.

- Newman, Eric P. The Early on Paper Money of America. 5th edition. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications, 2008. ISBN 0-89689-326-X.

- Wright, Robert E. One Nation Nether Debt: Hamilton, Jefferson, and the History of What We Owe. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008. ISBN 978-0-07-154393-4.

Further reading [edit]

- Brock, Leslie V. The currency of the American colonies, 1700–1764: a study in colonial finance and royal relations. Dissertations in American economic history. New York: Arno Press, 1975. ISBN 0-405-07257-0.

- Ernst, Joseph Albert. Money and politics in America, 1755–1775: a study in the Currency act of 1764 and the political economy of revolution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1973. ISBN 0-8078-1217-X.

External links [edit]

- Currency Bug to Overcome Depressions in Pennsylvania, 1723 and 1729

- Creating the U.S. Dollar Currency Marriage,1748–1811: A Quest for Monetary Stability or a Usurpation of Country Sovereignty for Personal Proceeds?

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_American_currency

Posted by: scottdess1993.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Money Was Used In 1616 In America"

Post a Comment